A Sense of Place

A photographic essay linking location, community and campus in the Copper Country |

Copper Mines and Miners

The Keweenaw boasts a long and storied history of copper mining. Men and their families came from all over the world seeking a better life in the mines of the Copper Country. It was tough work, and dangerous. Days were long and the work was grueling. The 1913 copper miner’s strike is the most famous of the many strikes by miners against the companies that controlled their lives in and out of the mines.

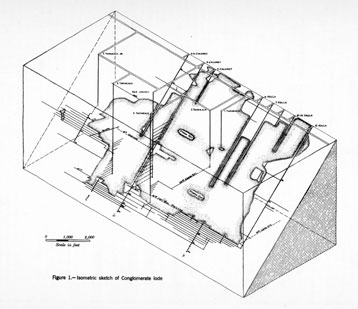

Isometric Sketch of the Calumet Conglomerate Lode

(Vivian, Deep Mining Methods, Conglomerate Mine of the Calumet & Hecla Mining Company, 1931)

TN443M5V5-002

|

|

Men and machines penetrated the hard rock of the Keweenaw in search of native copper. Amygdaloidal lodes yielded copper that had been trapped in the bubbles and fractures of dark basalt rock. In conglomerate lodes, copper formed in the spaces around sand and pebbles trapped in the rock. The Calumet Conglomerate Lode plunged almost 6,000 feet beneath the surface along an outcropping that extended almost two miles long. By the time this sketch was drawn, the rich lode produced more than 40% of the native copper mined from the entire district. |

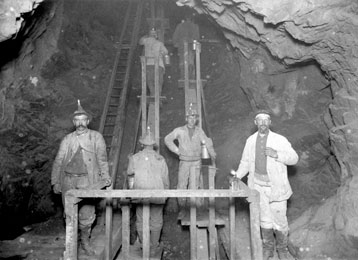

There were a number of ways to get workers down into the mine. In 1864, man engines began to replace ladders in the deeper mines. The reciprocating action was, in effect, a mechanized ladder, moving a miner more quickly along the shafts and conserving his energy for the real work of breaking copper from rock. Despite a lack of safety features, miners welcomed the man engine; especially those who made the grueling 1,000-foot climb twice a day at the Cliff Mine. By 1890, the more efficient man car replaced most man engines throughout Keweenaw copper mines. |

Man Engine, Quincy Mining Company, 1890

MTU Negative Collection

Neg 01062

|

|

|

Mining hazards weren’t limited to the dangers of working underground. The danger of explosions and fires was an ever present risk on the surface. The tremendous pressure generated by steam engines to power hoists and other machinery could build beyond containment. This fire at the brick and stone Superior Engine House in the 1880s was the result of an explosion in the heart of Calumet & Hecla’s industrial core. Sanborn Insurance Company maps documented the potential risks associated with industrial property and now provide a rich resource for researchers in the Michigan Tech Archives. |

Employment records offer detailed information about the men and women who worked for the mining companies above and below ground. Today, these records provide valuable data for genealogists and historical researchers. Information about ethnicity, immigration, housing, family members, and mortality rates are just some of details captured and preserved in mining company employment records preserved by the Michigan Tech Archives. The record of John Lakner reveals the degree to which underground workers had to rely on skill and experience for their own safety; his death was caused by “miscounting the reports of the firing of three block holes.” |

|

Trammers at C&H

Mining Engineering Photographic Collection

MTU012-015-720

|

|

Skilled and unskilled workers toiled underground, and particular ethnic groups were associated with various mining functions. The work of drilling and blasting was considered a skilled profession and experienced miners from Cornwall claimed a higher status than other workers. Eastern Europeans often worked as trammers, viewed as little more than human beasts of burden. Trammers loaded rock cars with ore and used brute strength to transport the cars to shafts to be hauled to the surface. Improvements in mechanized haulage decreased the need for human trammers after 1900, but C&H continued to use trammers for over a decade more. |

Keweenaw copper appears in layers of rock that strike down from the surface at roughly a 45 degree incline. Mine shafts pierced the rock vertically while drifts, or side passages, extended outward from the shafts. Stopes angled upward from the drifts, following the steep angle of copper bearing rock. Miners worked the ore, drilling and blasting the red metal from makeshift platforms erected in precariously slanted stopes. Despite the efficiency of the one-man drill, miners resisted the change from the two-man drill, calling the new drill a “widow-maker.” Their protest became a rallying point for miners during the 1913 copper miners strike. |

Underground at Tamarack Mine

Roy Drier Photographic Collection

Neg 00279

|

|

|

The 1913-14 copper miners strike marked a ten-month long period of violence and conflict in the copper mining district. At least 84 people lost their lives in the violent acts that occurred during the strike. Miners struck for higher wages, a return to the more familiar two-man drill, and unionization under the Western Federation of Miners. Big Annie Clemenc was an outspoken supporter of the striking miners and became an icon of the time. She led hundreds of strikers in parades against the mining companies, travelled throughout the Midwest raising money for striking mine workers, and was convicted for assault and battery against law enforcement officers. Her involvement was not unique; the Detroit Free Press reported that Copper Country women were “the heart and soul” of the strike. |

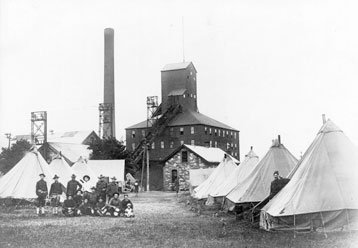

In response to Houghton County sheriff James Cruse’s fears of rioting and vandalism by striking copper miners, Michigan governor Woodbridge Ferris assigned Michigan National Guard troops to the embattled northern mining district on July 24, 1913. Troops encamped throughout Houghton and Keweenaw County, ordered by Woodbridge to “protect the life and property of the employee along with the employer.” During their six month stay in the Copper Country, the Michigan National Guard was not involved in a single fatality. On January 12, 1914, Governor Ferris ordered the last of the troops home, leaving the district in the hands of local law enforcement. |

National Guard Troops at Red Jacket Shaft

Nara Photographic Collection

Nara 42-153

|

|

|